Afterthoughts: In the Mouth of Madness

“Afterthoughts” is a Fear of God blog series featuring co-hosts and guests further unpacking thoughts, themes, and ideas that keep them up at night from the conversations and content covered on the show. This entry is by guest and FoG Legal Council, Dave Courtney, and is a follow-up article to this past week’s episode featuring In the Mouth of Madness. Enjoy, then, these afterthoughts…

“Reality is not what it used to be.” - John Trent (from In the Mouth of Madness)

“We are all of us hardwired for beauty, searching for a deeper and richer meaning in a world that sometimes seems to overflow with delight but at other times feels dreadful and cold. Beauty- the haunting sense of loveliness, the transient yet utterly powerful stabs of something like love but something more and different as well- is not after all a mere evolutionary twist, an echo of an atavistic urge to hunt prey, to find a mate, or to escape danger. It is a pointer to the strange, gently demanding presence of the living God in the midst of his world.” - N.T. Wright (from Broken Signposts)

“Things are turning to shit out there, aren’t they.” - John Trent (from In the Mouth of Madness)

I mentioned in the Fear of God Episode covering John Carpenter’s 1994 film In the Mouth of Madness that much of Carpenters’ filmography remains a blind-spot for me, which was simply to underscore that in choosing a film of his to discuss with the podcast hosts, I remained dependent on the synopsis.

So why did In the Mouth of Madness stand out for me? I was intrigued by the connection it was making between fiction and reality. The synopsis describes a fiction that is coming to life in the real-world in ways that result in a literal “Hell” on earth. Add in a dose of mystery surrounding the disappearance of this “hack" horror writer named Sutter Cane and a sleepy, New England town setting and I hoped — and expected — that it would resonate. The episode’s conversation makes clear that it did live up these hopes and expectations.

Perhaps the most noted part of our conversation surrounding this film had to do with parsing out this relationship between fiction and reality. The tension I noted in the synopsis plays out in numerous other related questions, not simply regarding the influence and power of art for potential good and bad, but also into questions about the nature of reality itself. If it is true that “reality is just what we tell each other it is” then this line between reality and fiction is far more blurry than many of us might have imagined. As Daniel Kurland says in an article discussing the film on Bloody Disgusting, perhaps the most noted observation about the story is not that it is depicting fiction crossing over into reality, but that “it’s about someone realizing their reality is fiction.” Further, what does this observation say about our ability to influence our reality. If reality is the stories we tell each other, does this leave us with more or less agency? Are we captive to the story or do we have the power to rewrite the story? These kinds of questions point to the essential human need for hope. When we look at the world and find that “reality is not what it used to be" and perceive that “things are turning to shit," what can we do about it?

Perhaps the biggest takeaway for me from the film and our ensuing discussion is that we can learn to tell a better story, and that hope holds the power to write a better reality. Or at least, it offered me a stark picture of what it is to lose hope. And as the contrasting quotes above demonstrate, I do think telling a better story begins with our ability to perceive the literal beauty that is also visible within the literal hell, learning how to grant the former more power as we attend to the latter. For Christians, I think this hope comes from an essential trust in the Christ story to make beautiful the ugliness of the world. The Gospel story was written so that we might make it a lived reality. This is the sense in which Christ as beauty and truth stands taller than that which occupies “the seat of an evil older than mankind and wider than the known universe”, a phrase which comes from Lovecraft’s “The Haunter of the Dark”. Where the film presupposes the question “when does fiction become religion?“ which is inevitably the point when things turn to shit, a more hopeful word able to reshape the film’s somewhat dire finish might be, “when does reality become Christ?” This is the phrase that gives us agency. This is the phrase that holds the promise of a better ending by way of establishing the opportunity for new beginnings. As Wright says in his book On Earth as in Heaven: Daily Wisdom for Twenty-First Century Christians:

"If the earth is full of God's glory, why is it also so full of pain and anguish and screaming and despair? Isaiah has answers for all these questions, but not the sort of answers you can write on the back of a postcard. The present suffering of the world- about which the biblical writers knew every bit as much as we do- never makes them falter in their claim that the created world really is the good creation of a good God. They live with the tension. And they don't do it by imagining that the present created order is a shabby, second-rate kind of thing, perhaps (as in some kinds of Platonism) made by a shabby, second-rate sort of God. They do it by telling a story of what the one creator God has been doing to rescue his beautiful world and to put it to rights. And the story they tell indicates that the present world really is a signpost to a larger beauty, a deeper truth." - N. T. Wright

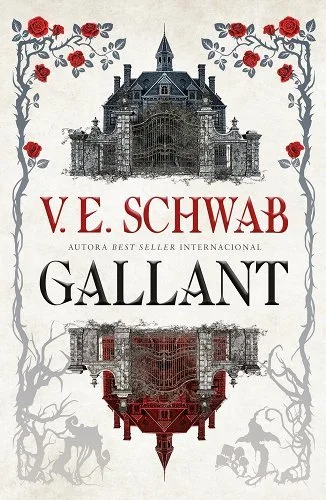

In the Fear of God episode, I cited the book Gallant by V. E. Schwab as my “watcha”, explaining my desire to delve back into fiction after being consumed by non-fiction over the past number of months. I loved the reminder host Nathan Rouse gave closer to the end of the episode that despite the power fiction holds to do damage, such damage comes only when we make fiction into a religion. This is the moment when we trade the true image of God, humanity and creation for a false one, reshaping reality according to a different narrative. Fiction in and of itself also holds power to give language and words to the good and the beautiful we otherwise wouldn’t be able to describe. Fiction can be a powerful tool for helping us to imagine a better, and thus truer, story.

I was struck by the relevance of the story in Gallant to this end. The caption on the back quotes this from the book: “Everything casts a shadow. Even the world we live in.” If In The Mouth of Madness depicts a world enslaved to the darkness, Gallant imagines a world where beauty and darkness are set side representing shared realities but reflecting different truths about reality. Inherent to its story is the ability to imagine how it is that beauty and goodness can bring hope to the hopeless places, thus becoming a light that is able to break into the darkness and reveal the truth about reality.

The story follows a young orphaned girl named Olivia Prior who remains unsure about who she is. The only thing she has is her mother’s journal, from which she encounters a cryptic warning not to go to Gallant, a stately manor with direct ties to her family name. When a letter suddenly arrives inviting her to return home she is left with a choice- heed her mother’s cautionary voice by staying at the orphanage or respond to the letter’s invitation by going to Gallant. The feelings of loneliness and lostness, the desire to find a “home” and to know the truth of who she is prove the more powerful forces, and so she commits to going. The story follows her then as she journeys into and through this inherent tension, discovering the secrets of Gallant and thus the truth of her own reality.

What I loved about this story, aside from it being a quick paced and highly engaging story, is how it allows us to imagine a reality that contains both darkness and light while offering its main character, and subsequently us as readers, a way to reimagine her story according to goodness and beauty. Instead of giving the darkness power, hope becomes the thing that is able to reveal the essential humanity that lies underneath; such as the loneliness she feels and her need to belong somewhere and to be seen and heard in her struggles. We can note this being expressed in In the Mouth of Madness as well as the driving force of what gives power to the darkness. Just as we find in the film, Gallant echoes the deeply felt cries to flee before it is too late, before the darkness of a particular narrative comes to write her reality in a way that leaves her bound to the shadows of these most basic human fears. “These dreams will be the death of me” is a sentiment that carries through the story with the sheer weight of these warning cries, steeped as they are in the darkness of Olivia’s journey, threatening to define her reality in one direction or another. And yet, to glimpse the shadows is to also begin to see reality for what it is, providing the basis for which to step into a more hopeful story, one that Olivia can begin to write only by way of participation in it, giving agency to her humanity and power to her sense of agency.

As a Christian, I think both of these stories brought clarity to my own sense of place in this grand story we call existence. I’m reminded of the image author David Gushee presented by citing his belief in a Christ that goes ahead of us, demonstrating the way to write a better story as He beckons us follow. This echoes the words of Yahweh to Israel in Deuteronomy 30:8 “The LORD himself goes before you and will be with you; he will never leave you nor forsake you. Do not be afraid; do not be discouraged." along with the final words of Mark’s Gospel in 16:7 “But go, tell his disciples and Peter, “He (Jesus) is going ahead of you…”

The comma in this passage provides an interesting portrait of how this idea becomes a reflection of hope. In one sense we could hear it as a contrasting word that stands in opposition to the darkness we perceive all around us. If setting off on the journey and embracing the possibility of new beginnings often means stepping into the darkness, the “but” in this passage beckons us to trust that Jesus has gone ahead, treading the path of this darkness in our place and declaring to us that there is in fact beauty to be found along the journey. At the same time, “but go" tells us that we cannot be complacent. We cannot simply sit in this promise and let Jesus do all the work lest the darker fiction become our reality rather than our reality becoming Christ.

We must journey.

We must learn to walk in the shadows. We must participate in the story in order for it to be made true in our lives and in our world.