Coraline and The Alice Allusion

“Afterthoughts” is a Fear of God blog series featuring co-hosts and guests further unpacking thoughts, themes, and ideas that keep them up at night from the conversations and content covered on the show. This entry is by frequent guest and Foreign Correspondent, Vera Goudie, and is a follow-up article series to this past week’s episode featuring Coraline. Enjoy, then, these afterthoughts…

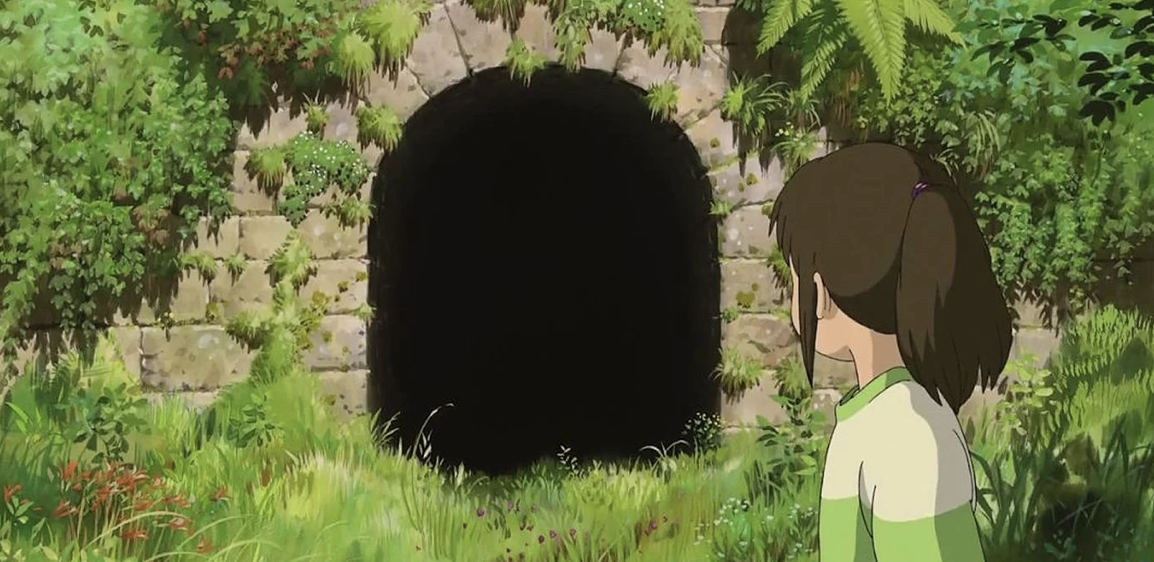

This is a story about a young girl, who is transported to a different world, faces peril, and returns home… I am, of course, referring to the Henry Selick directed stop motion feature Coraline. On the other hand, is it Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away? The past couple of weeks, the Fear of God has covered a couple of amazing movies where the narrative format follows a pattern we’ve seen over and over again dating all the way back to Wonderland.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was a novel written by Lewis Carroll, published in 1865. It gave us the story of the titular Alice, whose curiosity over a white rabbit leads her to fall down a rabbit hole into the fantastical and topsy-turvy world of Wonderland. Since then, the phrase “down the rabbit hole” has become a metaphor for adventure into the unknown; something that transports someone into a surreal state or situation.

Since its original publication, Alice’s adventure down the rabbit hole has become a narrative trope, where young children (very often girls), find themselves transported into a fantastical realm full of wonders (and often danger!). This is called the Alice Allusion, which is meant to invoke parallels to Carroll’s original work.

Alice aside, some of my favourites that fall into this trope are: Pan’s Labyrinth, The Wizard of Oz , The Lion The Witch and The Wardrobe, Labyrinth, Spirited Away, and of course, Coraline.

In order for a concept to become a cliché or trope, a format needs to be followed. In the Alice Allusion, the protagonist must be a child, there is a transition between worlds, the child will face adventure and/or peril, and then a transition back to the mundane.

As with Alice in Wonderland, Coraline Jones is a young girl. In Disney’s animated feature, Alice has been aged up a little to be 10 years old. In fact in all of the works cited above, the age range is from 10 (Alice, Lucy, Chihiro) to 16 (Sarah). There is a reason that children are featured so heavily in this genre: children are the embodiment of innocence. Their perception of the world around them has not been corrupted by adulthood. They are more willing to see and believe in magic than adults, and thus be able to access the magical realms that they (often quite literally) fall into. An important part of their journey is that they learn lessons throughout; it simply would not make sense to feature an adult protagonist in a coming-of-age tale.

The next important piece in the Alice Allusion is the transition between worlds. In Wonderland, as the saying goes, Alice falls down the rabbit hole. Coraline crawls through a tunnel to The Other House. Chihiro and her parents also transition through a tunnel. Dorothy is carried to Oz by a cyclone. Jareth transports Sarah to the Labyrinth. Ofelia also travels through a Labyrinth in the forest (although her actual transition happens at the end of the story), and Lucy finds Narnia in the back of a wardrobe. The transition is often (not always) through or by a mundane object in the real world. The world to which they transition is full of magic, wonder… and danger. Even in Labyrinth, where so much of the landscape is bleak (bog of eternal stench? No thank you!), it is a world full of magic creatures where seemingly anything is possible.

Important to their transition from the real world are the feelings that lead them there. The protagonists are often bored, frustrated with the mundane world, and have a propensity for curiosity. Alice is bored during her sister’s history lesson. She spots the white rabbit and lets her curiosity get the better of her, ending up in Wonderland. Coraline follows a similar pattern. Her family has moved to a new home, she is away from her friends, her neighbours are strange, and her parents do not give her the attention she is craving. She wanders and explores her new home, finding the little door and when presented with the opportunity, goes through it. Dorothy longs to fly over the rainbow like a bird, away from mean old Miss Gulch and her small farm life. And Lucy ends up in the wardrobe during a rainy day game of hide and seek.

In the next part of the Alice Allusion, the child faces the danger, perils, and adventures that the other world has to offer. Alice takes part in a series of vignettes. Eventually, she comes across the Queen of Hearts, who puts her life in peril by threatening to cut off her head. Coraline marvels at the creations of the Other Mother, which seemingly satisfy every complaint she has about the mundane world. However, she soon discovers there is a cost to remaining in this alternate world as the Other Mother informs her she must sew buttons over her eyes to stay. Coraline realizes that getting everything she wants is not worth the loss of her soul, and strives to return home. Sarah fantasized and romanticized the idea of the Goblin King until she accidentally gave him her baby brother when he would not stop crying. In order to save him, she must complete his challenge of finding her way through his magical Labyrinth or lose her brother forever.

An interesting feature that pops up frequently during the adventure portion of the story is food and its often negative effects on the protagonist. Alice runs into all sorts of problems with potions, biscuits, and mushrooms that frequently change her size. Not to mention the disastrous tea party she attends. Coraline is offered popcorn and cotton candy, cake, and all of her favorite foods prepared by the Other Mother to tempt her to stay. Ofelia is warned not to eat any food from the Pale-Man’s table, but succumbs to temptation when she eats two grapes, which awakens the child-eating monster. Chihiro’s parents eat the food of the other world, which transforms them into pigs, trapping them. And Lucy is betrayed by Mr. Tumnus when he uses teatime as a way to make her stay in Narnia so she can be reported to the White Witch as a Child of Eve. The inclusion of this motif is to remind us that part of the transition from childhood to adulthood is learning to control your figurative appetites. Children do not have the ability to limit their wants, in these worlds often to disastrous consequences. It is an important lesson for us to learn: that we should not get everything we want, and when we do, it is often to our detriment.

The adversity that the protagonist faces is often some representation of a childhood fear or a barrier to adulthood. Coraline, Sarah, and Chihiro fear losing their family members, whereas Alice and Dorothy fear that they will be lost forever, and Ofelia fears literal and figurative monsters.

Finally, the protagonist in the Alice Allusion must transition back to the real world. With the exception of Pan’s Labyrinth, which turns this last part upside down by having Ofelia truly enter the Underworld at the end, while having her interact with aspects of it throughout in the real, all of our main characters find their way back to their home. In doing so, they are wiser, more mature; the lessons learned through their peril having helped them in their coming-of-age. They have no need for the magical realms anymore, finding an understanding that what they had in the mundane one was the one truly worthwhile. Alice realizes that her “world of her own” was not as fun as she thought it would be, and that the rules and limitations of the mundane world exist for a reason. Coraline grows to appreciate that her real parents, though imperfect, are much more valuable to her than fabricated ones because they love her unconditionally. Dorothy, of course, learns that there is no place like home. And Sarah puts her selfishness aside and realizes she loves her little brother.

Interestingly, when our main characters return, they usually carry with them the tension of whether or not what happened was real or imaginary. Alice appears to be woken up from a dream, having supposedly been put to sleep by her sister’s history lesson. Dorothy also is woken up, having experienced a head injury during the twister. Coraline is set up so that her transitions between the real world and the Other World happen mainly at night, and so could be explained by dreams. When the Pevensies all return from Narnia unexpectedly, over time they start to believe that maybe they dreamed the adventure (in fact by book 7, Susan does not accompany the other Pevensies to the New Narnia because she believed it to be childish fantasy). Chihiro looks back at the tunnel after she frees herself and her parents, implying that she is questioning whether it all really happened. Even Ofelia, who has been shot in the real world, enters the glowing Underworld with The Faun, and we as the viewers are left to wonder whether it is really happening, or just the vision of a dying child.

Ultimately, I do not think it matters whether the events of the story truly happened or are the product of child imagination. Because the impact of their adventure leaves a lasting impression on the character, not on the world. And that is the important takeaway of any coming-of-age story: the lessons you learned along the way.

Now… so what? Why is this type of story so compelling? Why has the format carried on from 1865 to this day?

All of the elements of the Alice Allusion parallel a child’s journey to adulthood, and we love a good coming-of-age story. As adults, it is impossible to see the everyday world through the eyes of a child. Try as we might, even those of us with young children only catch glimpses of the magical and wondrous way our offspring view the world. They see what is beneath the surface, down the rabbit hole, or over the rainbow. This is the place where adventure happens.

When the child protagonist is placed in a magical world, it puts us in the same place as them. A place where we do not understand all of the rules and are waiting to see what happens next. We are allowed to briefly experience what it is like to be a child again.

I mentioned that very often (but not exclusively) the child protagonist is a girl. Why does it matter? Well, if we think back to Carroll’s original piece from 1865 there were certain societal expectations of girls. They had to be prim and proper, might have been doted on, and were expected to say or do very little. They certainly were not supposed to go on big adventures; that was for boys. A lot of the same expectations exist for girls today. But the girls in these stories don’t fit in with the real world. They might be considered odd, or weird, or loners. They have a tendency to be daydreamers, whose curiosity might get the better of them. There is definitely a cautionary tale for girls to keep their feet on the ground, lest they stumble beneath it. There is an argument to be made that the “down the rabbit hole” trope is meant as a warning to young girls to stifle their curiosity and to behave as they are expected to, or else. There might even be a commentary on the Victorian era views on females and the propensity for insanity and hysteria because of the uncertain nature of the actual existence of these realities. Return to Oz literally finds Dorothy committed to a sanatorium for refusing to acknowledge that she dreamed Oz. But as the mother of three young girls who loves and is drawn to these types of stories, what I find in the protagonists are positive qualities aplenty! Ofelia sacrifices her own life to save her baby brother. Coraline finds it in herself to be brave in order to rescue her parents and then make sure the key to the Other House is lost forever. Lucy joins her siblings in a literal war for Narnia while embodying compassion and forgivingness for Mr. Tumnus and his deceit. Time and again, these young girls prove themselves to be brave, resourceful, and compassionate. These are qualities that I want my daughters to see in the media that they consume.

Additionally, the child protagonist – with their innocence, curiosity, and naïveté – navigates their way through this new place, we understand that it mirrors the way a child navigates their way to adulthood. Through this journey, we understand that the fears and barriers they face are the things they must overcome to progress to adulthood.

Additionally, as the child – with their innocence, curiosity, and naïveté – navigates their way through this new place, we understand that it mirrors the way a child navigates their way to adulthood. Through this journey, we understand that the fears and barriers they face are the things they must overcome to progress to adulthood.

Being a cliché or a trope does not need to mean stale and overused. Fairy tales persist through time for two reasons: their story is compelling, and their messages resonate throughout the ages. It is why the Alice Allusion continues to see new iterations. From a somewhat zany tale told of Wonderland, or the technicolor marvel of Oz, these stories help children navigate the world with imagery that will capture their imagination and help them to process the fear and barriers they need to traverse in a way they can understand. And we get a glimpse down the rabbit hole, to the world just beneath the surface that we left behind when we grew up.